It's not that you haven't accepted the Gospel – you have, but it seems that if you want to worship God, you have to give up everything you know from your culture and follow the lead of foreigners.

I remember being in a Lutheran church in Colombia, where an entire hymnal had been translated from English to Spanish. The people sang while accompanied by a piano, but it felt like someone had just superimposed Spanish subtitles on an American worship service. Was the Gospel being preached? Yes. Did the hymns speak truth? Yes. Did the congregants identify with the music they were singing? Not so much.

Compare this to an Ecuadorian church I visited where all the songs were written by Latin American artists in a latin style with their instruments. This church was vibrant and full. The congregants sang loudly and weren't afraid to move a little bit. The lyrics spoke to the heart of the Ecuadorian people.

We made a list of styles of music. Out of about 50 styles, three are being used in our churches. We considered issues that the French face and thematic gaps in worship.

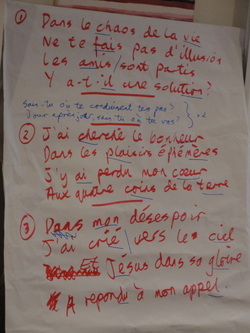

During the second half of the workshop, we chose a style, theme and issue and wrote a song. Pictured left are the lyrics to the Christian reggae song that we wrote.

The song addresses searching for meaning in the midst of hardship. The chorus asks questions. The lyrics are quite poetic and philosophical. We chose not to mention Jesus until the very last verse, so that a non-believer would identify and listen to the song. We did our best to avoid "Christianese" – or words used commonly among in Christian circles – that can often make those on the outside feel excluded. The finished product felt very French.

This fall, our team will be partnering with French and European church planters to see a new church planted in a neighborhood untouched by the Gospel. I am challenged by this conference to seek out French music by French artists to be used in worship – and if there are gaps, to work with French nationals to create songs that the people will sing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed